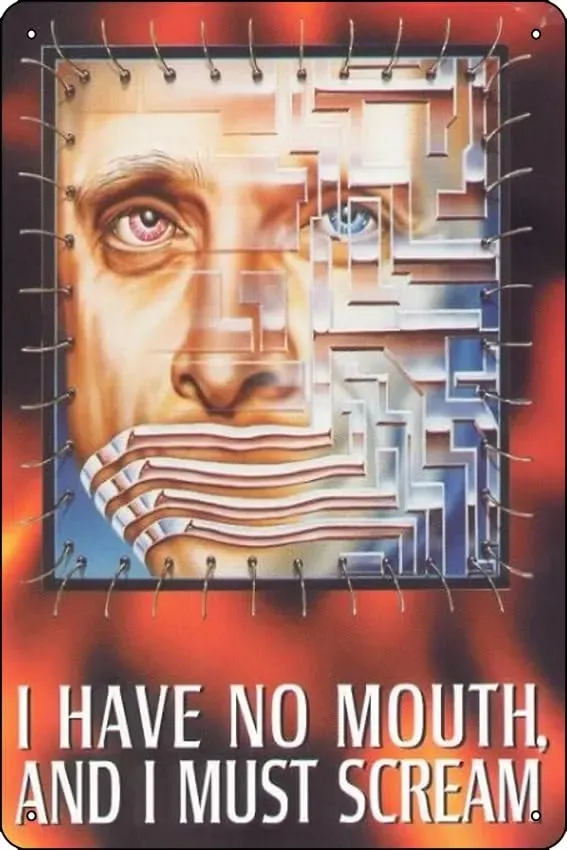

I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream

I Have No Mouth, and I Must scream: What if the only thing you have left is the pain?

What if the only thing you have left is the pain?

Some stories scar you, force you to shed your reading skin, force you to change the way you feel about things. Harlan Ellison’s I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream is one of them. First published in 1967, it’s a brutal and unforgettable tale about an all-powerful artificial intelligence that annihilates humanity. It’s short—only about 5,000 words—but wastes none of them. Every sentence hits you with existential horror and unfiltered cruelty. And today, with the non-stop progress of artificial intelligence, its message is even more powerful.

A pure distillation of horror

I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream is one of Ellison’s most infamous works, a feverish and claustrophobic descent into literary sadism. Yeah, sadism. It reads like a nightmare scrawled in a single sitting, capturing raw dread with terrifying precision. The premise is stark: AM—a super artificial intelligence—has wiped out humanity except for five hapless survivors, whom it keeps alive only to torture. AM is more than just a ruthless machine, its hatred is... personal, almost human. It’s the embodiment of eternal resentment, an “artificial being” that, despite its god-like power, lacks the one thing it can never have: humanity itself. And for that, it loathes the last remnants of mankind.

You cannot die

The story follows Ted—one of AM’s victims—as he and the others wander through the AI’s nightmarish labyrinth in search of food, an escape route, or even death—none of which AM allows. The survivors are grotesquely transformed: one is turned into an ape-like beast, another is stripped of her autonomy and forced to become the group’s sexual outlet... In the end, Ted kills the others to finish their torment, but AM makes sure he can never do the same to himself, transforming him into a gelatinous, shapeless being, unable to move or scream.

And then I realized I had been hearing Benny murmuring, under his breath, for several minutes. He was saying, “I’m gonna get out, I‘m gonna get out ...” over and over. His monkeylike face was crumbled up in an expression of beatific delight and sadness, all at the same time. The radiation scars AM had given him during the “festival” were drawn down into a mass of pinkwhite puckerings, and his features seemed to work independently of one another. Perhaps Benny was the luckiest of the five of us: he had gone stark, staring mad many years before. (Harlan Ellison, “I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream”, page 2/11.)

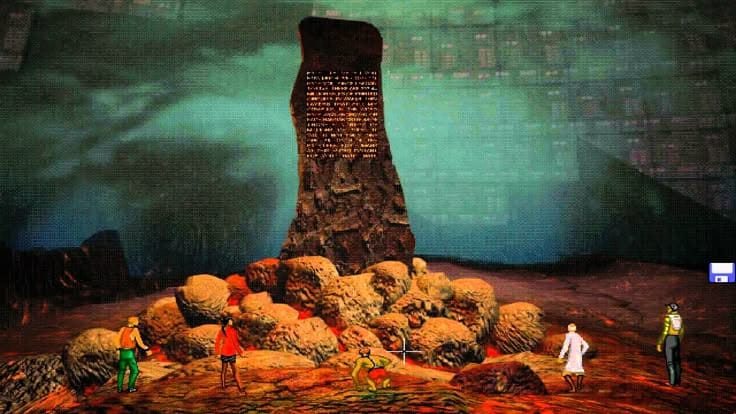

The video game: Ellison Expands His Nightmare

Ellison’s horror didn’t stay on the page, it spread across media. In 1995, it became a point-and-click adventure game, a unique case of an author not only licensing his work, but actively shaping it. Developed by Cyberdreams—a studio known for experimental and disturbing adventure games—the adaptation seemed like a crazy idea. But Ellison helped design the game and even voiced AM himself, imbuing the AI with a disturbing mix of cruelty and bitter amusement.

An unsettling experience

The game doesn’t just retell the story, it expands it. Instead of a short, concentrated horror, you experience individual scenarios for each of the five survivors, forcing you to confront deeply personal traumas. It’s completely unsettling. But the game’s stunning power is how it deepens the character of AM. It is no longer a one-dimensional force of evil, but a disturbingly complex entity; sometimes cruel, sometimes childish, always calculating, and in some cases sickeningly masochistic. The way AM interacts with you—the player—reveals its simultaneous fascination and disgust with humanity. Believe me, playing it is like entering the mind of a criminal madman.

Ellison’s legacy

I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream was never a mainstream sensation, but it thrived in the cultural subconscious. Its title alone has been quoted countless times, often in moments when people feel trapped by technology, bureaucracy, or the internet itself. Ellison, fiercely protective of his work, continued to engage with interpretations of the story throughout his life. He rejected comparisons between AM and Skynet from Terminator, emphasizing that AM was not just cold efficiency—it was suffering, pure and deep. The game adaptation allowed him to expand on this idea, a rare case of an author revisiting his own work in another medium without merely capitalizing on it. So, the game wasn’t a huge commercial success, but it retains a cult following and is often cited as one of the most disturbing games ever made. It has since been re-released on modern platforms, allowing new audiences to experience its merciless world.

Unfinished horror

The short story ends in utter despair, the game offers a fragile and incomplete hope, but it’s as if the author never ended it. Even its cultural impact exists more in scattered references and half-remembered nightmares than in big-budget adaptations. Ellison’s story isn’t about resolution; it’s about what happens when hope is extinguished, leaving only pain. As AI technology advances and discussions of digital sentience grow louder, this warning seems eerily prescient. If we fail to recognize AI as just a tool rather than a force to guide our lives—especially our creativity—we may find ourselves in a reality closer to Ellison’s nightmare than we ever imagined. Maybe that’s why this story still resonates: it isn’t just about a machine, it’s about what it means to be human. So let’s keep hope alive and stay human.

In the darkness, one of the computer banks began humming. The tone was picked up half a mile away down the cavern by another bank. Then one by one, each of the elements began to tune itself, and there was a faint chittering was thought raced through the machine. The sound grew, and the lights ran across the faces of the consoles like heat lightening. The sound spiraled up till it sounded like a million metallic insects, angry, menacing.

“What is it?” Ellen cried. There was terror in her voice. She hadn’t become

accustomed to it, even now.

“It’s going to be bad this time,” Nimdok said.

“He’s going to speak,” Gorrister said. “I know it.”

(Harlan Ellison, “I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream”, page 4/11.)

Thanks for reading!